When we heard that senior dog Jake is thriving with a combination chemotherapy to control his osteosarcoma lung metastasis, we wanted to know more. And now, you can too! Join us for a fascinating look at how monthly chemotherapy with Palladia and Carboplatin is helping Jake live his best life on three.

Senior Tripawd Cancer Survivor Jake Introduces Us to Combination Chemotherapy

In September, Jake’s dad joined the Tripawds Discussion Forums to share Jake’s story and ask questions about low platelets on his latest lab report:

Greetings Tripawd Community – our beautiful dog Jake, who was 14 in June lost his left front leg to Osteosarcoma one year ago today and one month after the amputation he started Carboplatin drip Chemo every month since.

We also started him on a Chinese herb shortly after the amputation to help fight the cancer – Wei Qi Booster, 2 x daily.

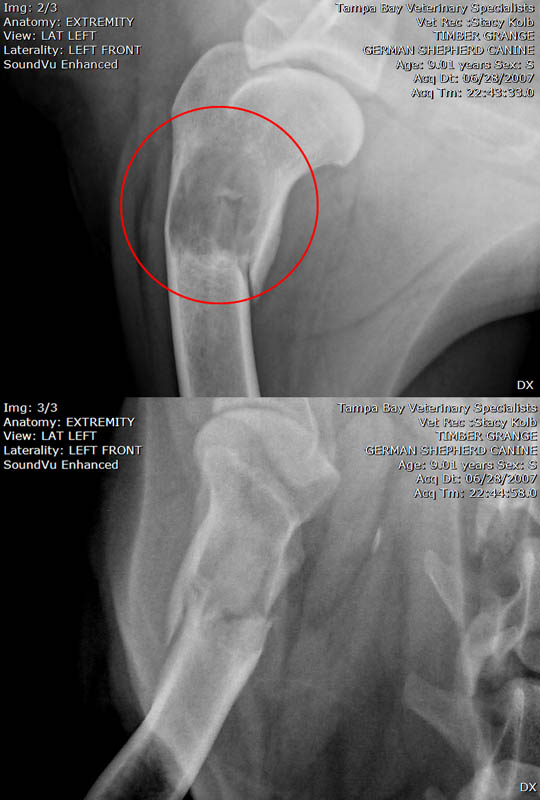

When they did the first follow up x-ray on him in late December they saw 2 small nodes on his lung and decided to add Palladia 3 x a week in addition to his monthly Carboplatin therapy. Since then he has had 2 rounds of x-rays (each 3 months apart) and it he has been all clear no signs of the Osteosarcoma thankfully.

He has been tolerating both meds very well, really no problems at all. So the Oncologist moved him to 2x a week on Palladia back in June. READ MORE

We did a double take when we read Jake’s treatment. Giving a dog with osteosarcoma an ongoing, low dose of oral chemotherapy at home isn’t unusual. That’s known as metronomic chemotherapy, and it’s been around for years. But monthly doses of Carboplatin? With Palladia too? That’s the unusual part. And Jake is thriving because of it!

Why Combination Chemotherapy is so Unique

Most osteosarcoma dogs get four to six doses of intravenous Carboplatin. Then they move on to metronomic chemotherapy using another type of chemotherapy, typically cytoxan or leukeran. The goal is to prevent and slow down metastasis. Sometimes metronomics works. Sometimes it doesn’t, and is slowly falling out of favor with some oncologists.

When we heard that Jake was getting this “combination chemotherapy” treatment, we had to know more. We reached out to Jake’s oncologist, Dr. Brooke Britton from New York, and she kindly agreed to this interview for Tripawd Talk Radio.

If your dog or cat has osteosarcoma, download the Tripawd Talk Radio podcast episode:

Or, watch the Tripawd YouTube video about combination chemotherapy for dogs

You can also read the full transcript below.

And if you’ve tried this treatment, please comment below or in this Forum topic. We’d love to find out how it worked for your Tripawd.

Transcript: Combination Therapy for Canine Cancer with Dr. Britton

Welcome and thanks to Tripawd Talk Radio Episode #105 with DR. BRITTON.

Today, we are going to be talking about some innovative canine cancer, limb cancer treatments including monthly chemotherapy for dogs with osteosarcoma.

And we are excited to have Dr. Britton help us understand some of these cutting-edge therapies. Dr. Britton is a Certified Veterinary Oncologist with a degree from Cornell. She trained at the University of Pennsylvania and practiced with BluePearl for several years. We discovered her work when a Tripawd’s member posted about their dog, Jake, in our discussion forums. And we will let her tell you all about that and more. Thank you for joining us, Dr. Britton.

DR. BRITTON: My pleasure. Thank you so much for having me.

TRIPAWDS: Can you tell us just a little bit about yourself? And why you decided to focus on oncology? Especially those creative therapies?

DR. BRITTON: Absolutely. From a personal standpoint, unfortunately, I had experience with cancer as a very young girl. My brother was diagnosed with a brain tumor when I was very small. Seeing him go through that diagnosis and my parents go through that diagnosis. His treatment and everything that came along with that and having such a love for animals from a very young age. That interest in oncology and why cancer can be so difficult to treat. Why there are different theories about how to treat it? And how to successfully treat it and how far technology and treatments have come in the past several years. I found it intriguing to be able to help companion animals. As well as their people through a process like this.

Wanting to be a veterinarian since a young girl and having that experience at an early age, I think was very formative for how I choose to use my veterinary education. And then my chosen specialty. It’s not a specialty that everyone would imagine someone initially going into because of the subject matter that we deal with. But it’s an incredibly rewarding. Contrary to what most people might believe, it can be a very, very happy space to be in this specialty.

TRIPAWDS: We always thought it (chemotherapy) was one and done pretty much. You do that series of carboplatin treatments and that’s it. You go on. You do metronomics if you want or not. And you hope for the best.

So when Jake joined us, it was really interesting because he just casually mentioned that you were treating him with monthly intervals of carboplatin. So that kind of blew our minds. I thought I heard it mentioned before but not so much. So can you tell us why you decided to start doing it that way for Jake and do you do it for other patients or is it just particular ones?

DR. BRITTON: Yeah, that’s a great question and there’s a lot to unpack. The science and the medicine has become more sophisticated over the years. We have more options and research extrapolated. And also real on-the-ground research in companion animals with these compounds and from human medicine. We’re starting to understand that we can treat dogs and cats not exactly the same as people, but with similar drugs and even with combination therapy. Which is what I have been doing with Jake.

To your point about his specific protocol, typically you’re right that carboplatin is usually given for about 4 to 6 total treatments. Usually at about 3-week intervals intravenously in a dog or in a cat with osteosarcoma. And typically after a limb amputation.

With carboplatin over time (as with many chemo and other agents), you can start to see changes in their blood counts, their platelet counts, white cell counts. For that reason and because we don’t know that a maintenance type chemotherapy or long-term or indefinite chemo makes a difference and many of these dogs and cats, we pick that number to stop.

We say we will do 4 to 6 and then we monitor them. Then if they develop complications later or progression of their disease, we may restart or try something else.

The reason why I choose to keep going with Jake but amend the protocol was because he actually developed pulmonary or lung metastasis.

The concern would be that the carboplatin was enough to keep those at bay for a time. But not enough to prevent them from happening. We saw that change on chest x-rays. Jake actually was feeling fine, maybe a couple of very subtle changes if we look in retrospect in his behavior. But generally, an excellent quality of life.

It was soon after we had stopped that initial course of carboplatin which was initially my intent with him. What we did was amend the protocol by adding in a different type of agent. Which is the fully approved drug called Palladia or toceranib phosphate is the drug name. And that’s a different class of drugs called small molecule or tyrosine kinase inhibitors, TKIs.

Admittedly, we don’t have a lot of evidence to know exactly what is the ideal patient to combine those therapies in. Or what is the ideal dosage when you combine those therapies. Or what tumor types respond best to the combination.

We know that there’s a basis for treating patients across multiple tumor types with those types of drugs. Alone or in combination with traditional chemo like carboplatin.

But all of the data isn’t fully flushed out yet. And that sort of again speaks to your other point about some of the other oncologists that you may have spoken to that have different levels of comfort with using combination therapy or things like metronomic chemotherapy.

Not all of the data is fully mature. Sometimes we don’t have much data at all. That’s where we have to have a long and informed conversation with companion animals’ people.

What does this mean if we start to combine therapies? What are the potential risks or the potential benefits?

I would be very upfront about we don’t know exactly. What this outcome will look like if we combine these therapies. But I think something that I emphasize when I’m doing things, that I don’t necessarily have 5 published papers to point to to say, “This is the expectation.” Because sometimes we just don’t know and it’s very individual. Sometimes it works for certain patients. Sometimes it doesn’t for others.

The most important thing overarching all of this is quality of life. As long as we are making adjustments as we go along, we are not using experimental agents per se. These are approved agents. We are just using them in a way that we don’t necessarily have hundreds or thousands of patients of data to say, “This is the outcome we can expect to a 90% certainty.” If that makes sense.

As long as we are upfront about that and have that conversation and we put quality of life at the forefront, I think that that’s the most important thing. To make sure that people understand and have realistic expectations. Then if they want to go forward and try those options, we can change or stop at any time based on on that. We can amend the protocol as we need to or change or stop again.

The really lovely thing about Jake was that he generally felt amazing on the combination of drugs that we chose. In his case, it actually clinically worked very well. His pulmonary metastases regressed on the combination therapy.

The reason we are sort of spreading out that carboplatin to every 4 weeks is that sometimes when you combine these therapies, they have increased risk of side effect. You may want to spread out or alter your kind of traditional single-agent approach when you’re combining things. To make sure that it’s well-tolerated and to preserve their bone marrow.

Just like in people, we tend to see this less in dogs and cats. But if we use really high doses or we combine a lot of things together, that can have an effect on their bone marrow cells. And the healthy cells in their body. Which can become limiting or prohibitive down the line. We want to make sure that he can continue to get treated. That he has a high quality of life. And that his body is not getting tired of the combination.

That was a very long answer to your question. But that’s a lot of what went into kind of tailoring that protocol to him. And it’s not necessarily the same exact protocol that I would use for a dog in the similar situation. It’s very much tailored to that individual patient.

TRIPAWDS: when you say combination chemotherapy, was the Palladia you added given in conjunction at the same time during the same session as the carboplatin? Or alternated? Or did this cause the need for additional visits? How exactly did that look in the clinic?

DR. BRITON: Yeah, that’s another great question. Palladia is an oral drug like many of these TKI drugs in its class. Typically, a person that’s going to be giving this drug at home to their pet about 3 to 4 times a week on average. That applies for both cats and dogs.

Usually, I start out about 3 times a week and then I can adjust as needed. Sometimes we need to taper down to twice a week. Sometimes we need to adjust the dose. And we often will adjust the dose to the very low end f the dose range if we are combining it with chemo. And we adjust the chemo dose down too. To a lower dose than we would do if we were giving it by itself.

In the beginning when you first combine them, there is more potential to see changes. Not only in their appetite or their energy level. Which may decrease at least initially, but you can see more changes in their blood counts as well.

We may have been every 3 to 4 weeks with carboplatin by itself. Then we may tighten it up to every 2 to 3 weeks. When we add the Palladia in in Jake’s case, we were seeing him once a month when he was due for his injections. Then we were taking full blood work at that time, which suffice for both the chemo and the oral drug monitoring.

Over time once you see how the body tolerates it, you can spread those visits out. But initially, they did tighten up a little bit for Jake. Just to make sure that he was tolerating everything well.

Another point I would make is Jake’s age. Jake is a prime example of the fact that he was an older dog when he started. He is an even older dog now. But when he started, he was enjoying and still enjoys a really robust quality of life.

Even though he is older, he was tolerating these medications very, very well. Hs older age doesn’t necessarily mean that he is less likely to tolerate any particular drug or a combination of drugs.

Jake really did succeed and has continues to succeed in life in terms of his attitude. Just like humans, companion animals have a variety of different personalities. They are individuals. It’s not just statistically do they do better with a front or a back leg. Or do they do better if they’re a smaller dog versus a bigger dog and how old they are. I think all of those things take a distant second to:

- the personality of their person and their people

- their family and support network

- and their own personality

Jake really, despite being an older dog, really had a zest for life, which continues to this day.

A lot of people say, “Well, look, my dog is older. I don’t know if I want to put him or her through all of these procedures. Regular visits and drugs and chemo sounds scary. I had chemo or my family member or friend had chemo and that sounded terrible or didn’t work or I had friend who had a dog who went through chemo and it didn’t work.”

The important thing is not to try, on my end anyway, not to try to pressure people to say chemo is great. Or we must do this. Or amputation is the only way. We have to come up with a plan that works for everybody. And most of all, the individual that we are treating, our cat and dog patients.

It has to work for everybody and everyone has to feel comfortable. At the end of the day, even if I think something is going to work out great, everyone has to be on board.

Going through that with open and frank communication with people, having a plan, and knowing that we can change a plan as things go along I think is really important to communicate to people. There are lots of emotions surrounding all of this. In addition to the physical and financial commitment of doing these treatments. It’s important to understand that people can change their minds. It happens a lot. And both ways. Some people said, “Well, I would never do any of these things.” And then they end up doing all the things.

In Jake’s case, I’m just really thrilled that he has had such a great experience. That he is successfully treated. And happy because all he thinks about I think most of the time, is the fact that he is able to enjoy his 3-legged life. Doing what he wants to do.

TRIPAWDS: When it comes down to the Palladia being given at home, are there any particular precautions and what specific side effects might be coming from that?

DR. BRITTON: One always has to use caution with oral chemotherapeutics or drugs like TKIs. even though they are not technically chemotherapy. We often will take chemotherapy-like precautions, so wearing gloves. We don’t want people to be exposed to a lot of powder or residue from the pills. To err on the side of caution, usually pregnant women, children, or immunocompromised individuals ideally would not handle those drugs. And again, that’s not even abundance of caution. In reality, the risk to those individuals is extremely, extremely low.

In terms of normal day-to-day, if a cat is using litter box, they can still share a litter box with their catmates. Oftentimes, it’s nice if there’s a bin liner or certainly a scope. Or some way of cleaning the box where your bare hands are not involved, which I think most people do anyway.

With a dog, picking up excrement or feces with a bag as they normally would. Or if the dog is urinating outside, there’s nothing special that needs to be done there. If they are urinating on wet pad in the house, ideally wearing gloves. Or washing profusely with soap and water one’s hands after they pick up a wet pad and disposed of.

Most of the hygiene practices at home can pretty much remain unchanged. There is always no issue with wearing gloves but at the same time, most of the times, people don’t absolutely have to wear gloves or put hazmat suit on to dispose …

TRIPAWDS: Does that hold true for women who are pregnant?

DR. BRITTON: Immunocompromised, or pregnant women if they are handling the drug directly, wear gloves. I recommend that people wear gloves when they are directly handling the drug. I’m talking about the waste material. When you’re handling the drug, the safest thing to do and the recommended thing to do is always to wear gloves.

TRIPAWDS: Is there an ideal scenario for starting a protocol like this? And can it be used in place of the initial rounds of chemo if somebody wanted to do that?

DR. BRITTON: I believe Jake had 1 to 2 metastatic lesions that we could see on plane films or x-ray. If we had done let’s say a CT scan or a more highly-sensitive task, we may have found additional smaller metastases that x-ray may not have been able to pick up. Given the fact that we saw the mets on plane x-rays, doing a CT wouldn’t have necessarily given us any additional information to change what we do.

Once we saw the metastases, we knew we had to do something different. That’s why again, we chose to use the Palladia. In terms of the threshold for metastases and when I would choose this, even if I would have seen several, several metastases or diffused metastatic disease, I would have still offered that protocol. I would have been more concerned in terms of outcome. Because of the repetitive and how those metastases developed over such a short period of time. And how extensive they would have been.

But I have seen dogs and cats with more widely or diffused metastatic disease that have had regression when I tried combination therapy like this. So I still think it’s worth putting it on the table.

TRIPAWDS: Why aren’t more oncologists trying this?

DR. BRITTON: Palladia was initially approved for, and again, when I say Palladia, I mean the brand name for the drug, toceranib phosphate. Palladia was initially approved for as you likely know mast cell tumors in dogs. because it’s fully approved, it can be used legally off-label for other species. And for a wide variety of tumors.

I think understandably and rightfully so, some – many – oncologists are reluctant to use Palladia as sort of a catch-all. We use “standard of care,” which is what carboplatin would be considered standard of care for – because we have much data to support its use for osteosarcoma.

But we lack unfortunately, well-controlled perspective clinical trials using Palladia in combination with different drugs for other tumor types.

I think again rightfully so and oftentimes, not just the academic oncologist but oncologists in academic scenarios, university scenarios, are reluctant to prescribe Palladia for every different tumor type. Because it’s sort of – we try as much as we can to practice just like in human medicine, evidence-based medicine.

We want to make sure that there’s a reasonable basis to believe that it (combination chemotherapy) could work. Not just, “OK, well, we will just try this and throw it at the wall. And see if it sticks because we are having progressive disease now.”

I think that we have enough data on Palladia. What it does is hit different types of molecular targets that in a way, it is targeted therapy. But it’s not as targeted as people think. And it hits many more targets that are not necessarily unique to mast cell tumor. It hits targets that are used in signaling pathways in a variety of different tumor types. So that’s why some oncologists, myself included, will use it for many different tumor types.

That sort of grey area is where communication is very, very important. I tend to give a lot more information to people. I say, “This is what this drug is in a nutshell. This is the basics of what it does and the broad strokes of what we hope to achieve. And here’s the data that we have for it.” It’s mainly for another tumor type or maybe for two or three different tumor types.

Right now, we don’t have a lot of data to support its use here and we might even have a paper here or there that says, “We tried it and it didn’t work in this particular patient population in the study,” which might have been 5 dogs or 10 dogs or 15 dogs. And we know in human trials, hundreds of patients are often in those papers that are published unless it’s a very, very rare tumor type. But osteosarcoma is generally a very common tumor type.

That’s the important thing to highlight. That’s why you get a variety of different opinions. It doesn’t mean that I’m right and another oncologist is wrong. Or the academic oncologist is right and the private practice oncologist is wrong. It just means that you have a variety of different comfort levels. It’s not a bad or a wrong thing to do. It just may not have as much data to support it.

Some oncologists might say, “I’m not going to do it unless I have 20 papers that say that 80% of these patients will benefit,” and other oncologists say, “It’s not proven not to work and it’s not overtly harmful.” And we know in some circumstances, both anecdotally and in publication that it can.

The important thing to note again is that what we really need and are always striving towards, is actually putting this down on paper. To give more people the confidence and the comfort level to do it by designing these trials. Which is a whole other story that requires a lot of funding and a lot of other things that are for a different session.

TRIPAWDS: What inspires you as an oncologist to try treatments like this with patients?

DR. BRITTON: Things like combination therapy are very widely used in human medicine. And again, the difference is that the data. They struggled with the same things that we do. But the data in large part is there with more patients in these trials than what we have.

We can extrapolate and say, we know that this can work. In trying to push veterinary oncology forward and offering more sophisticated therapies, there has to at least at first a basis for can this work? If we combine them and then we have to get the data to back it up and support it so that it may or may not become standard of care. I think that that’s always what we are striving for.

I get inspiration every day just from my patients and wanting to do better for them. If there’s anything that I can think of to do that is grounded in solid science and as much evidence-based as I can find, I’m willing to push the envelope a little bit. Not to put them in harm’s way or to experiment. That’s not what we do. But thinking outside of the box is important. It’s important because it pushes the science and the medicine forward. Ultimately, it results in better treatment and more options for people who want to explore this type of process with their companions.

TRIPAWDS: Thanks for your time!

Many thanks to Dr. Britton for the cutting-edge work she is doing to help dogs and cats with cancer. Learn more about chemotherapy, Palladia, immunotherapy, and the full spectrum of veterinary oncology treatments available in the Tripawds news blogs and join the discussion to find out about Jake or share your story in the forums at Tripawds.com.

Thank you for tuning in. Subscribe to Tripawd Talk Radio for more pet amputation tips from experts and claim your free gift just for listeners at Downloads.Tripawds.com/Podcast.