Many pets lose a leg after multiple fracture repair surgeries trying to save it. But a bone regeneration technique being researched at the University of California at Davis could help future pets with non-healing broken legs avoid amputation.

Dr. Amy Kapatkin and the orthopedics team at UC Davis are regrowing leg bones with a new technique using a material called Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP). This cutting-edge bone regeneration procedure can actually regrow leg bone in pets with fractures that won’t heal using traditional methods. The UC Davis team has performed it on about 40 pets so far and today, Dr. Kapatkin gives us the details of how it’s done.

How Bone Morphogenetic Protein Saved Ethel’s Leg from Amputation

What is bone morphogenetic protein? Can it be used instead of amputation for treating broken legs in pets? Today, you’ll learn how BMP helped Ethel, a tiny 2-year old Yorkshire Terrier. Ethel had a broken leg that wouldn’t heal despite multiple surgeries. When her people heard that BMP could be an alternative limb sparing surgery option for their beloved dog, they turned to one of the world’s experts on the procedure, Dr. Amy Kapatkin, Professor of Surgical and Radiological Sciences at UC Davis.

In Episode #86 of Tripawd Talk Radio, we continue our interview series with faculty members at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Today, Dr. Kapatkin discusses Ethel’s case and the work she is doing with BMP, to save broken legs in pets. Learn learn all about BMP, how it works, and when it can be used as a limb sparing surgery option.

Here’s Ethel, happy to have all four legs!

Check out all of our discussions with UC Davis faculty at Tripawds.com/tag/UCD.

Want to learn more about BMP? Listen to the full, unabridged audio version of our conversation with Dr. Kapatkin on Tripawd Talk Radio.

No time to watch the video? Read the transcript below.

Transcript: All About Bone Regeneration for Pets

with Dr. Amy Kapatkin

KAPATKIN: I’m Dr. Amy Kapatkin and I’m a professor of Small Animal Orthopedic Surgery here at the University of California Davis. In my position here, I do at least 50 percent clinical time. I do some clinical research, and teaching and service to the university in outside organizations.

Meet the First BMP Dog Patient, Ethel

TRIPAWDS: Can you tell us more about Ethel?

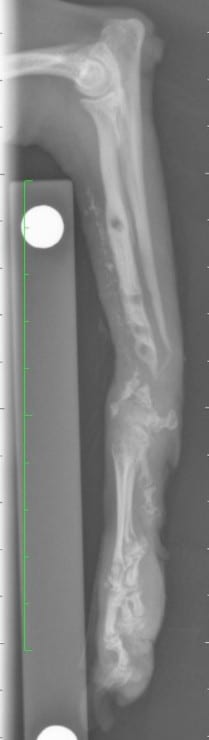

KAPATKIN: Ethel came to us after she had been rescued by great owners who understood that she had had two fractured front legs, both radius and the ulna. She is a tiny dog. She weighed about 2 kilograms. She is a little Yorkie, Yorkshire terrier, very scared, very nervous dog that when they adopted her, one of the limbs that had been repaired had gone well. It had a bone plate and had done well. The other one also had a bone plate but had many, many surgeries on it, constant failures either at the plate or on the bone.

When she found me, she actually found me because she was researching ways of looking at how to repair this leg and actually have success because pretty much all the surgeries that had been done before were done correctly but we do have complications. And on these tiny little dogs, the bone plates are although fairly rigid, they can break the bone that’s tiny.

And although everything had been done, standard of care of redoing it, making it rigid using autogenous bone graft, all those things had been done in Ethel and had failed in this one leg. And the owner was very intent on trying to find solution and she had found something online that in the University of Glasgow, they were looking at some sort of mesenchymal regenerative treatments for limbs that failed in both healing.

At the time, she was ready to go to Glasgow but they said, “Well, there’s someone in California. You live in California. There’s someone in California doing work.” So, that’s how she got to me. And the way we gone involved with bone morphogenetic protein is that one of our dental surgeons here, Dr. Arzi and also Dr. Verstraete, they worked with Dr. Reddi who is actually the very first person who discovered how to take bone morphogenetic proteins and produce them. He is at University of California Davis. And they were working on regeneration of bone for cancer patients of the jaw.

So they had successfully used it by resettling large pieces of the mandibular and maxillary and then rebuilding that in a bone plate and bone morphogenetic protein on a scaffold. So we had decided that we were going to try this in long bones and because it’s only a research product, we had to get approval which we did from a company and why we started using it in some of these patients that standard of care and multiple surgeries have not worked in. So this was how Ethel got here to us and how she found us.

So specifically with Ethel, she was a challenging case. One, she only weighted – she weighed less than 2 kilograms and she was a very nervous dog, very excitable dog. The owner said it’s almost impossible to keep her quiet. And I explained to them that was going to be a part of the recovery and that what had happened was she was – her radius was so tiny by the time they came in here and the distal part of the radius was virtually gone, the bone resorption, these are hugely bones with very large bone gaps. And I knew I would have to put the plate across to her metacarpal bones. What happens to dogs who don’t use bone is the bone starts disappearing so her carpal bones had started resorbing, her metacarpals were tiny. We call it disappearing bone disease. When you don’t have weight-bearing, the bone disappears.

There was a ONE PERCENT CHANCE her leg would heal with BMP bone regneration!

And so, she had that problem and I was very concerned that her metacarpal – I knew I had to put the bone plate across there, basically fuse the carpus. The metacarpals were so tiny and the bone quality was very, very poor. So my concern was that the bone plate would not hold. Bone morphogenetic protein, we’ve been very successful at producing bone, but it also – you need stability of the area.

I gave her a very guarded prognosis because Ethel at the time was our smallest dog. She is not now. We have done two smaller dogs. But at the time, she was our smallest patient with probably some of the worst bone that we had seen.

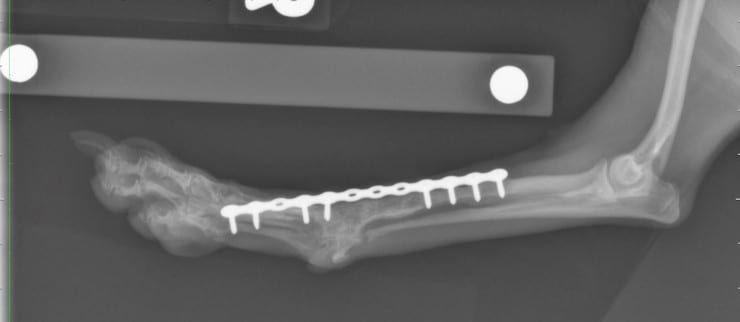

She took that chance and said, “No, I still want to go forward.” And we had discussed – and Ethel was really my very first patient that I said, “You know what? If we are going to have success, we got to keep her in the hospital and keep her confined because you are telling me you can’t.” And so, we made that agreement and we went forward with the surgery and we were able to get the bone plate on and used a large scaffold with the bone morphogenetic protein and keep her in the hospital and teach her to be a good dog, which she learned and it was ultimately successful.

Ethel was sort of our first patient, we said, “OK, now we take the next big challenge on because she was quite small.” And once again, dogs can get along with a fused carpus. You can put a bone plate across. It’s not our first line obviously but it certainly can be done that way.

TRIPAWDS: What is the actual name of the procedure or technology you used?

KAPATKIN: Well, the procedure really is you are fixing a fracture. Standard of care, and I should make this clear, standard of care is autogenous bone graft when you have missing bone or if have small gaps or you haven’t had multiple failures. And it’s basically bone plating with regenerative help from a scaffold with bone morphogenetic protein. And so, it’s not really any special procedure except for the fact that regular grafting hasn’t worked so we were using a different type of product.

TRIPAWDS: And where are the proteins from?

KAPATKIN: They are removed from bone and we use RH2 BMP. There are different BMPs out there. And not to get too technical, but they are really precursors to make mesenchymal stem cells react to produce either cartilage or bone, and whether cartilage or bone or sufficient bone and cartilage gets produced, it has a lot to do with surrounding cells dosage that must be on scaffold.

There are many, many technical aspects of it because it has to be used wisely. It’s not one of those things we can inject it or using more is better. In fact, that’s how it gotten a lot of trouble was incorrect dosing. And luckily, because of our dental service here that had used it, we had worked out the appropriate dosing that was highly successful without causing excessive bone production which is almost just as dangerous as no bone production.

This is “Off-Label” and UC Davis is the Only Vet Hospital Allowed to Use BMP

TRIPAWDS: What should pet parents know about this technology? Is the Davis the only one doing it? Are there other institutions out there who are doing it?

KAPATKIN: So I think what’s really important is that bone morphogenetic protein is not commercially available for veterinary patients. It is extremely limited in human surgery that were some setbacks when it was first used in the spinal – in the human spine surgery. FDA pulled it off the market and it is on the market for a very, very limited, very, very specific procedures like human surgery.

We, as far as I know, we are the only veterinary clinic institution in the United States that has access. And once again, it’s on research contract. We can’t send it out. So the cases have to come here.

Now in Europe, there are a few groups that I think have access so that it’s out there but in the US, there’s really not sufficient access to it. I make that quite clear. And once again, it’s not standard of care. The standard of care is this is for those cases that have failed. Many of the cases that come here have had five, seven surgeries with chronic failures with standard of care already. So these are not for the routine fracture cases.

TRIPAWDS: Who is the ideal patient?

KAPATKIN: The ideal patient is a dog that the owner feels they really want to keep the limb. Obviously, we push the envelope. We’ve had one kilogram dogs now. It’s an owner who really is tolerant of leaving the dog in the hospital potentially for a month to six weeks especially if they can’t control the dog and someone who is willing to take risks and have setbacks.

The last two patients I did had complications even after the BMP and had to have second surgeries. Ultimately, they did fine. But they have to be prepared that everything we do is not “standard” and so we have to accept that we are always trying to push the envelope on this to save the limb that it could fail. I mean I always tell people it could fail. I don’t promise success. I mean we’ve been incredibly lucky with our success. Out of all the patients we’ve done, one dog years later that they finally decided to remove the limb because the dog was having chronic infection problems and they didn’t want to go through more surgery. But other than that, we’ve been so far hundred percent successful.

TRIPAWDS: Great. And how many dogs?

KAPATKIN: I haven’t counted recently but it’s over 30 and maybe 40 patients have been treated.

TRIPAWDS: Do you ever see it use in cats?

KAPATKIN: Once again, we are sort of using it off-label. Cats are very off-label. There was one cat we tried it on and that cat was successful. Once again, we have owners sign when we use it in cats or we use it in one alpaca. We have them signed because it is very off-label and I can tell you it has been successful in both.

When Will Bone Regeneration with BMP Become Commercially Available?

TRIPAWDS: This is fairly still a research phase. Would you see this becoming more widely available and that kind of thing?

KAPATKIN: I think we would love to see this widely available. We know it’s successful in these clinical patients. Obviously, it could be terribly abused, meaning that it shouldn’t be really the first line. It’s very expensive. If you were to buy it, it’s a thousand dollars an ounce. If used incorrectly, it can cause severe problems. That’s what happened in the human field. They were using it in spine fusions. They put too much. So much bone grew. People could not swallow or breathe through their trachea and esophagus. People died from it.

There’s no question. It has to be used properly. It’s not a product that’s right out of the bottle that you just use. Dr. Arzi personally takes the responsibility of allocating it, making sure everything is done sterilely and correctly. It’s not like you take an injection and you just put it in. It’s not quite that simple but it has huge potential. I would love for it to be on the market because right now, many there are very qualified surgeons who have to send these cases here. It’s not that they can’t do the same thing I’m doing. It’s the question of we are not allowed to send it out so they have to send the patient to us. And it would be great if others could benefit.

TRIPAWDS You mentioned a plate and scaffold. What is the actual logistics of how it is applied and done?

KAPATKIN: Standard surgery where you take a nonunion. You have to debride the bone back to bleeding bone. You must have adequate bleeding bone to make this work well. Usually, that leaves you with quite large gaps. Most of these dogs have gaps already. Then it’s applying an appropriate implant for the right size that’s stable enough just like you would for any fracture. And then we go ahead and sterilely prepare the aliquot of the BMP on to the appropriately sized scaffold sterilely. Cut the scaffold to what we wanted the compression to resist the metrics. And then we press it in the defect.

You also have to handle it very carefully because once you contaminate instruments or your gloves or anything with this pretty much everything you touch will turn to bone. So you have to handle it carefully. It can induce even soft tissues to turn to bone. So you do need to handle it quite carefully.

And then with closure of the wound can sometimes be a challenge with these dogs that have had many surgeries and there’s not a lot of soft tissue surrounding just the limbs. So in the last patient we did, we actually had to do a skin graft which was the very first time we tried that in a little 1-kilogram-dog to close it because there has to have a closed environment. It can’t be used in an open fracture. It has to be a little bit closed.

TRIPAWDS: And what is the material of the scaffold?

KAPATKIN: Well, no. The scaffold is there to hold the bone morphogenetic protein in place to start to form bones. The scaffolds are usually gone in about four weeks. They just disintegrate and it’s – once again, it’s there strictly to hold the BMP. It is somewhat resistant to compression which is designed so that it’s firm enough where it helps give some scaffolding there without just completely collapsing down and then getting only the bone morphogenetic protein in one little area. It needs to be able to hold its shape for enough time for the BMP to work.

TRIPAWDS: That’s fascinating. Thank you so much.

KAPATKIN: You’re welcome. Hopefully, it was helpful.

[End of transcript]